By Zachary Dembo

Continued from Part I…

Our tour guide Milton Goldstein next took us on the Elton B. Stephens Expressway (US 31/US 280) as we headed downtown. Much of the city’s past, present, and even future can be viewed from the route. The most dramatic view is the Red Mountain Expressway Cut — an incredible geological spectacle of exposed mountain strata showcasing hundreds of millions of years. Exposed by the blasting of the route through Red Mountain in the 1960s, each layer tells a story about geological and biological forces forming the iron ore and limestone used by Birmingham’s iron industry and for the city’s construction.

The iron, limestone, and coal prevalent in the area attracted industry, which in turn meant opportunity. The influx of people seeking a new life included Jews like Milton’s family, who would go on to form the community to which we now belong.

Synagogues

Further down the Red Mountain Expressway and with Birmingham’s downtown visible we entered the Magic City’s southside. It is here that that a more or less forgotten, yet quite significant, chapter in the history of the Jews of Birmingham developed.

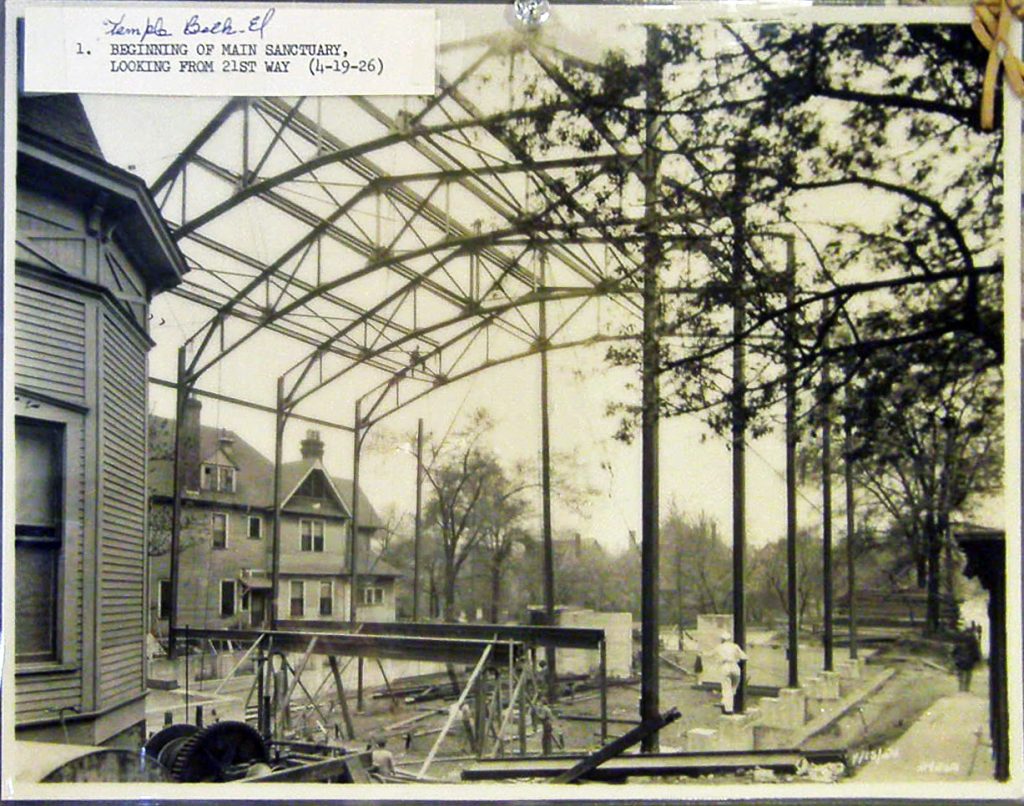

Here along the west side of the highway sits a synagogue, Temple Beth-El — the first visible evidence during our tour that Jews had made this city home. Built without needing any permission from a ruler and with materials bought from capitalists not kings, Temple Emanu-El and Temple Beth-El have origins that are well documented. At 113 and 99 years old, respectively, they are the oldest continuously used Jewish houses of worship in the city.

Another interesting aspect of Birmingham’s Jewish community is that many Jews belonged to both synagogues if not all three at the same time: Temple Emanu-El, Temple Beth-El, and Knesseth Israel (which no longer has a physical synagogue). According to Milton, this is a practice that although unheard of in many cities continues to this day in the Magic City.

Milton also confirmed that it was there, in and around the Five Points South neighborhood, where the synagogues now sit, that the second oldest concentration of Jews in Birmingham blossomed. While his family and many others were living in and around Fountain Heights, prominent Jewish families — including at first the Klotz, Saks, Burger-Phillips, Loveman, Adler, and Marx families — moved into the fashionable neighborhoods we viewed from our position on the highway. These southside neighborhoods enabled these almost exclusively “German” jews to escape the industrial pollution, crime, and overcrowding of the rapidly growing northside community.

According to my research, the first few Jewish families who built their homes along Highland Avenue in the late 1880s and early 1890s were soon followed by more northside “German” Jews (read more about this group). A third wave of northside residents, Jews of Eastern European background, moved into the homes west of 20th Street South before a fourth and final wave of “Russian” Jews relocated to the south side in the 1930s. However, none of these included Milton’s family, who, like many others, moved directly from the north side to Mountain Brook.

It was these migrating groups of Birmingham’s Jews who, enamored with their surroundings and wanting to be closer to the temple in which they prayed, helped finance the moves of both Temple Emanu-El and Temple Beth-El to their current locations.

A stone’s toss away from Beth-El on, 14th and 15th avenues south, was the home of lay rabbi, poet, and champion of education for all Birminghamians: Samual Ullman. Restaurateurs Louis and Blanche Gelders also lived on that block. Their son Joseph became a prolific labor and civil rights activist who was murdered by Alabama Klansmen. Their daughter Emma became a prolific writer and champion of numerous progressive causes.

Highland Park opulence

Driving a bit further north took us past Highland Park. Although most of the opulent mansions have been long since demolished and those that remain were obscured from our view by the foliage of Highland Avenue as it meanders along the curves of Red Mountain, it is here that some of the most successful and prosperous “German” Jewish families in the city lived during the first half of the 20th century.

Among the illustrious Jewish residents were many of the proprietors of the businesses that formed the heart of the retail district that we were heading toward. This included New Ideal owner Robert Z. Aland, both Saks Department Store owners Herman and Louis Saks, and Loveman, Joseph & Loeb co-owner Moses V. Joseph. Philanthropist Louis Pizitz, owner of Pizitz Department Store, also made his home on the mountain.

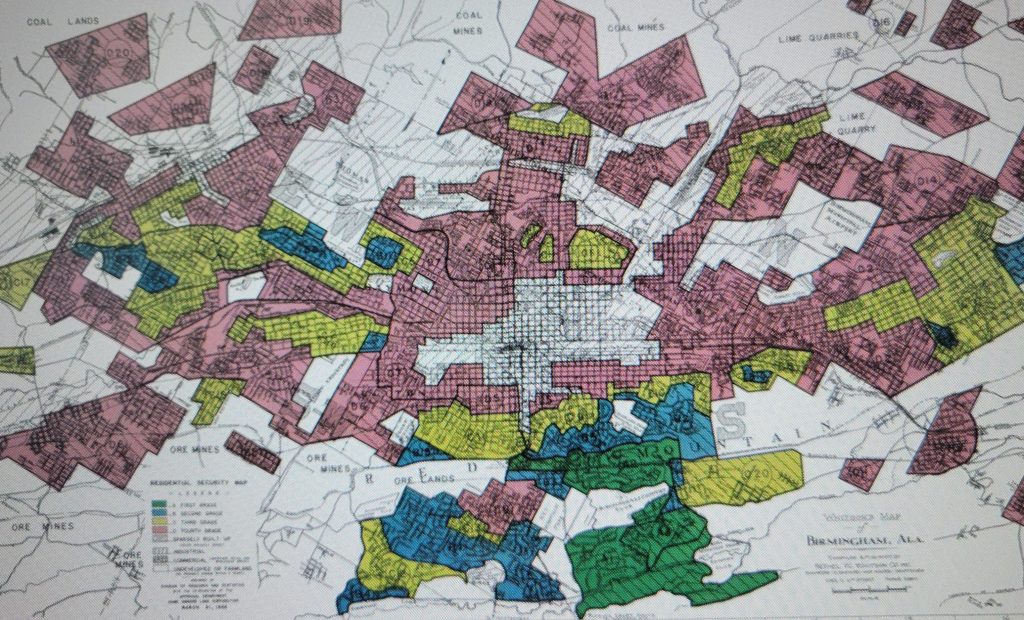

Redlining the Jews

Even further to the east, far beyond what we could see from the highway, is the Forrest Park Neighborhood and the “better part” of Crestline Heights, which according to redlining maps had a slow “Infiltration of Jewish families.” During the 1920s these highly restricted neighborhoods only allowed the most politically powerful and wealthiest Jews to become residents, specifically a few families involved in scrap iron, mining, and banking.

These neighborhoods are also notable because they became the last “high-class”neighborhood that even German Jews would be allowed to buy property in until Jewish developers started building homes in the gilded ghetto of Mountain Brook.

Stay tuned for the third and final installment of this tour series as we visit Birmingham’s downtown retail district, the old JCC building, and the city’s main Jewish cemetery…

Zachary Dembo is a Licensed Professional Counselor and Southern Jewish history nerd from Baltimore, Maryland — the Birthplace of the Star-Spangled-Banner. His first of many visits to Birmingham began in 2008 and he became a resident in 2019. He is married to Lauren Axelroth, a third-generation Birminghamian.

In recognition of Zach’s historical writing for The J’s blog in 2024, in January he received the LJCC’s L’Dor V’Dor Award “for embodying The J’s core value of empowering others to learn and understand Jewish values, thereby ensuring a vibrant and meaningful Jewish future.”