By Zachary Dembo

From America’s earliest days of independence through the end of World War II, many American Jews saw military service as essential to their success and acceptance in the new nation. Because Jewish loyalty was often questioned, participation in America’s armed forces became a powerful way for both immigrants and native-born Jews to prove their patriotism to their neighbors and to advance in American society. Activists fighting for Jewish protections and social acceptance considered Jewish soldiering to be fundamental to their cause. For more than a century these figures devoted immense energy leading massive wartime recruitment drives and fighting for the integration of Jews into America’s culturally Protestant armed forces.

Yet sometime after WWII, Jewish participation in soldiering became increasingly less important to American Jewry. The celebration of the American Jewish soldier — a ubiquitous feature of Jewish communal life since the Civil War — was gradually supplanted by celebrations of Israeli soldiers. By the 1970s, when the study of American Jewish history became recognizably academic, historians themselves often overlooked or even dismissed outright the importance of the Jewish soldier in the diaspora.

Historian Derek Penslar attributes this cultural shift to “Two sets of historically contiguous events: the Holocaust and establishment of the state of Israel on the one hand, and the 1967 Middle East war and the anti-Vietnam War movement on the other.”

The Holocaust, Penslar explained, had laid bare for the world’s Jewry that patriotic service in a nation’s armed forces for the purposes of acceptance and protection was “futile and misguided.” Then with the establishment of the state of Israel, the image of the “diaspora Jewish soldier as the epitome of Jewish masculinity and valor” was replaced by the mighty and, by 1967, stunningly victorious sabras of the Israeli Defense Force. Jewish opposition to the American involvement in Vietnam led Jewish activists to condemn both the U.S. military and Jewish participation in soldiering.

Yet despite this shift in focus, the historical record is clear: for 250 years American Jews have fought in and died for American causes.

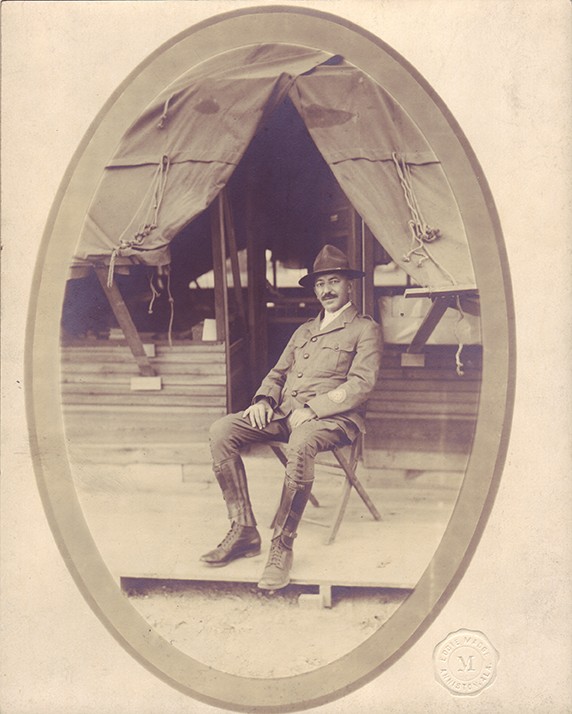

During the American Revolution they served in disproportionately high numbers. In the War of 1812 they endured the unceasing bombardment of Fort McHenry as part of its garrison, and captured British ships on the high seas as privateers. In the Civil War they rallied retreating troops under fire in the Virginia Wilderness and laid waste to the industrial heart of Alabama during Wilson’s Raid. They fought the Apache resistance in Arizona and fought hand-to-hand to capture Fort Rivière, Haiti, in 1915.

During World War I, Jewish Americans served at possibly the highest rates of any ethnic or religious group. In WWII they served with distinction in every theater and on every continent touched by the war.

Even after the eyes of American Jewry had fixed themselves upon the soldiers of Israel, American Jewish soldiers continued to serve with distinction. Since WWII, five have received the Medal of Honor — the highest award given by the United States military. More importantly, all five earned this distinction not only for defeating the enemy or engaging in the mutual responsibility | arevut inherent in military service, but by saving the lives of many | pikuach nefesh rabbim and in some cases facing certain death | mesirat nefesh.

Ultimately these acts of bravery, these moments of kiddush hashem | reflecting positively on the Jewish people, along with countless others unrecorded and unrecognized, remind us of a simple truth: Jews fight too.

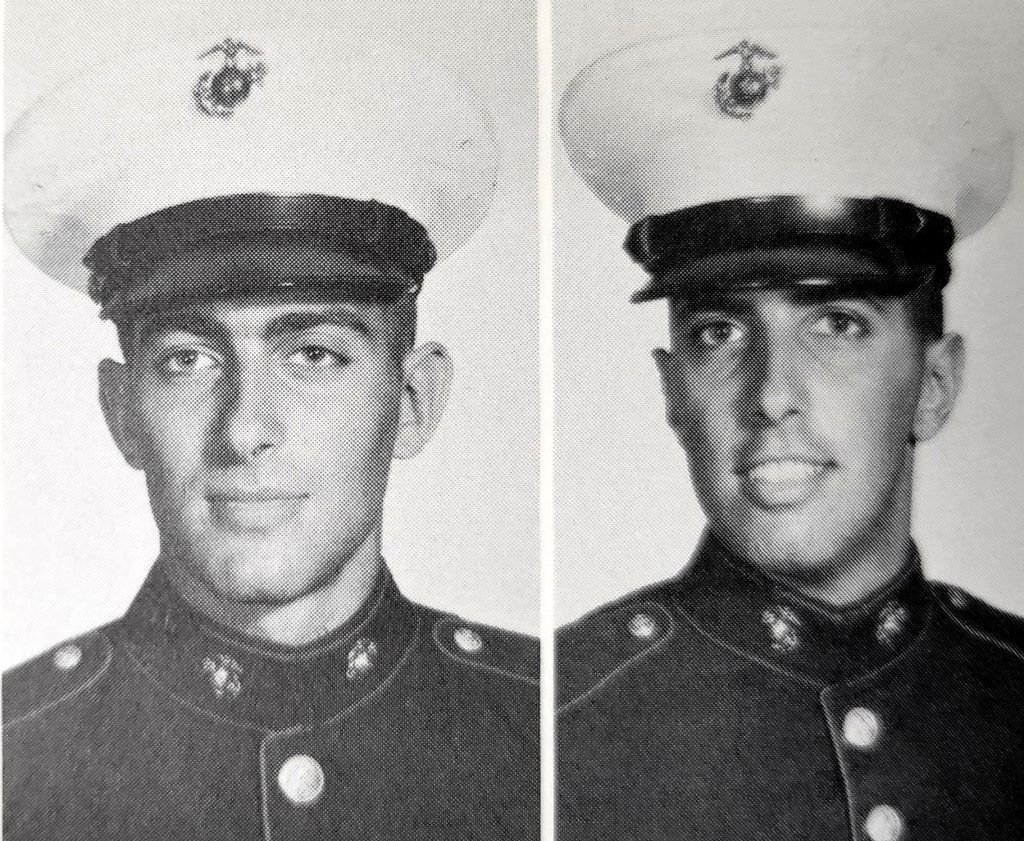

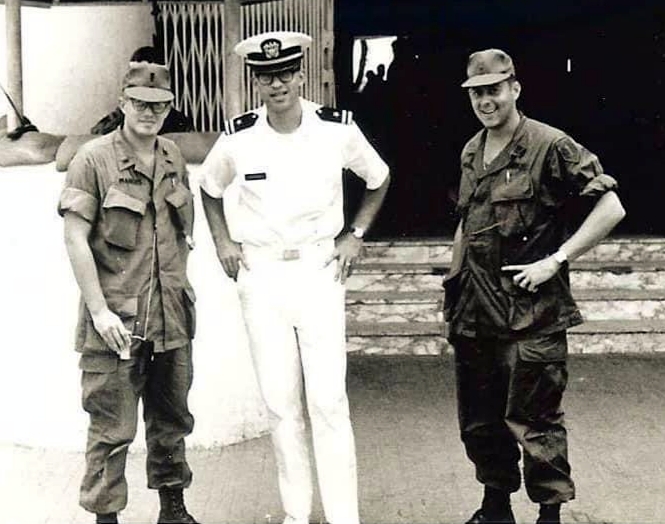

This national truth echoes loudly in the city and suburbs of Birmingham, Alabama, where Jewish men and women likewise stepped forward in times of war. From the first cries of “Remember the Maine!” to the deserts of Iraq, their service is part of American, Jewish, and Birmingham history. Evidence of these sacrifices are all around us: on display in the library at The J, inscribed on the graves in our cemeteries, and included in the biographies of our leaders like WWI veteran Mervyn Sterne, activists like D-Day veteran Edward Friend Jr., businessmen like WWII POW Albert Sokol, and important religious figures like Morris Newfield.

Like all other stories of service, the Jewish experience must be remembered alongside the larger national narrative. If you or members of your family served in the armed forces, we invite you to share those experiences with The J so that together we can honor and remember the sacrifices of our community (simply scroll down to access our survey).

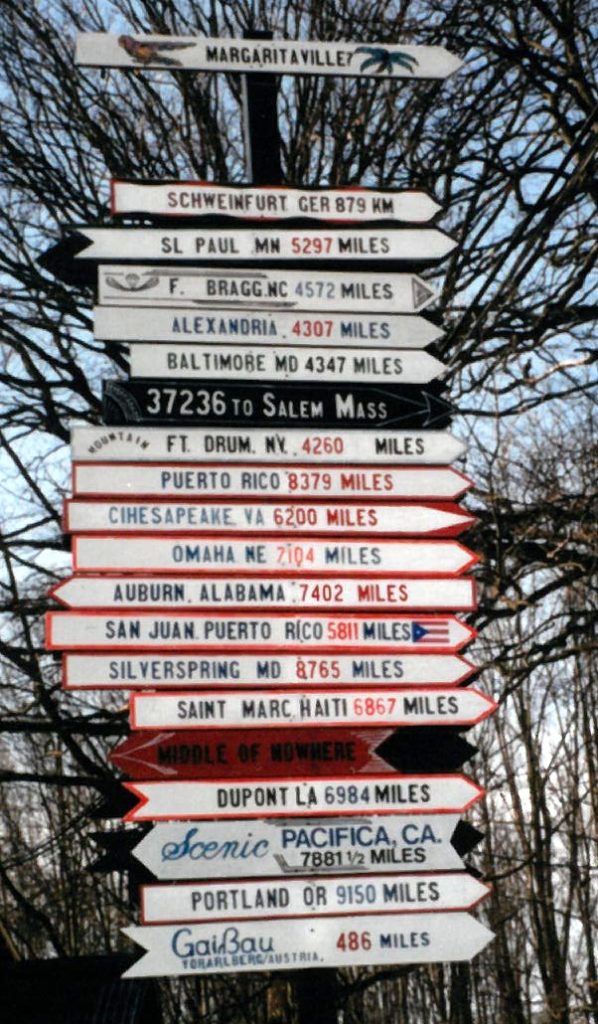

Auburn University at the time.

Our thanks to Milton Goldstein, Herb Rosenbaum, Bob Rutstein, and Phil Teninbaum for use of their photos.

Zachary Dembo is a Licensed Professional Counselor and Southern Jewish history nerd from Baltimore, Maryland — the Birthplace of the Star-Spangled-Banner. His first of many visits to Birmingham began in 2008 and he became a resident in 2019. He is married to Lauren Axelroth, a third-generation Birminghamian.

In recognition of Zach’s historical writing for The J’s blog in 2024, in January he received the LJCC’s L’Dor V’Dor Award “for embodying The J’s core value of empowering others to learn and understand Jewish values, thereby ensuring a vibrant and meaningful Jewish future.”

Also by Zachary Dembo:

- ‘More like brothers than friends’: Remembering WWII’s Jewish American war dead

- Touring Jewish B’ham with Milton: Part I, Part II

- ‘The Merchants’ make their mark

- Because we could: The history of Jews in Birmingham

- Of secrets, omissions, and selective memory

- How the ‘German’ Jews got to Birmingham: Part 1

- ‘I understand freedom more than you’: German Jews in Birmingham